In 2023, the Sentencing Council consulted on driving disqualification. The following factors were said to be relevant to determining the length of disqualification.

Special reasons and driving without insurance

The burden of establishing 'special reasons' is on the defendant. The standard of proof is the balance of probabilities.

In the context of insurance cases, the defendant must show that he was in some was misled. An honest but mistaken belief can only amount to 'special reasons' if there were reasonable grounds for that belief. In Rennison v Knowler [1948] 1 KB 488, it was said that the defendant is duty bound to make himself acquainted with the contents of the insurance policy.

If 'special reasons' are found then the court has a discretion not to endorse. It can either endorse the appropriate number of penalty points or not endorse. The appropriate number of penalty points must not be fewer than those set out in Schedule 2 of the RTOA 1988. In insurance cases, that means 6, 7 or 8 points.

Before court proceedings are instituted, the matter can be disposed of by paying a Fixed Penalty. In such circumstances, 6 penalty points would be applicable.

If the matter is prosecuted then there is an unlimited fine (many online sources get this wrong). A driver may expect 6-8 points unless they:

- were involved in an accident in which damage or injury was caused; or

- gave false details; or

- never passed a driving test; or

- were driving a goods vehicle; or

- were driving for hire or reward; or

- there is evidence of sustained uninsured use

In which case, disqualification from driving for up to 12 months may be appropriate. N.b. disqualification is not limited to 12 months.

See the sentencing guideline for further info: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/magi...

If court proceedings are commenced, usually via the Single Justice Procedure, then expect a fine, prosecution costs and a surcharge. Those items taken together will very likely far exceed the Fixed Penalty offer.

The burden and standard of proof in exceptional hardship cases

You must prove, on a balance of probabilities, that there would be “exceptional hardship” if disqualified from driving.

You will be required to take an oath (or affirmation) and speak about your circumstances.

It is your responsibility to provide the court with evidence to support your case.

Almost every disqualification involves hardship for the defendant and the defendant’s immediate family.

Hardship or inconvenience is not exceptional hardship.

Loss of employment is not itself sufficient to demonstrate exceptional hardship.

Whether loss of employment amounts to exceptional hardship will depend on your circumstances and the consequences for you or other people.

You will be asked about alternative means of transport.

If the court finds exceptional hardship then it has a discretion to order no disqualification or disqualify for less than the minimum period.

If the court does not find exceptional hardship then it must disqualify the defendant for at least 6 months.

Source: Sentencing Council guideline

Courtroom 75 and Courtroom 77

Courtroom 77 at a Magistrates’ Court is a Single Justice ‘court.’ This is typically a review hearing to disqualify in absence after the defendant has been sent a Notice of Proposed Disqualification. It is not possible to appear at a Single Justice hearing. Hearings of this type are ‘behind closed doors.’

Courtroom 75 is usually a Single Justice ‘Court.’ Cases may be adjourned from courtroom 75 to courtroom 77.

What is the difference between careless and dangerous driving?

The actus reus of dangerous driving is driving in a manner which falls far below what would be expected of a competent and careful driver in circumstances in which it would be obvious to a competent and careful driver that driving in that way would be dangerous. “Dangerous” refers to a danger either of personal injury to any person or of serious damage to property.

The actus reus of careless driving is driving in a manner that falls below what would be expected of a careful and competent driver. This may merely cause annoyance or show lack of consideration, with little risk of injury or serious damage.

The difference between the two types of offence is the extent to which the offender’s driving falls below the required driving standard; namely “far below” for dangerous driving but merely “below” for careless driving.

The CPS website lists a few examples of what is, arguably, careless driving:

- overtaking on the inside

- driving too close to another vehicle

- driving through a red light by mistake

- turning into the path of another vehicle

- the driver being avoidably distracted by tuning the radio, lighting a cigarette etc.

- flashing lights to force other drivers to give way

- misusing lanes to gain advantage over other drivers

The Magistrates Court Sentencing Guideline lists the following culpability factors for careless driving:

- Excessive speed or aggressive driving

- Carrying out other tasks while driving

- Tiredness or driving whilst unwell

- Driving contrary to medical advice (including written advice from the drug manufacturer not to drive when taking any medicine)

Similarly, the CPS website lists some examples of what is, arguably, dangerous driving:

- racing, going too fast, or driving aggressively

- ignoring traffic lights, road signs or warnings from passengers

- overtaking dangerously

- driving under the influence of drink or drugs, including prescription drugs

- driving when unfit, including having an injury, being unable to see clearly, not taking prescribed drugs, or being sleepy

- knowing the vehicle has a dangerous fault or an unsafe load

- the driver being avoidably and dangerously distracted, for example by using a hand-held phone

- lighting a cigarette, changing a CD or tape, tuning the radio

The MCSG lists the following culpability factors for dangerous driving:

- Disregarding warnings of others

- Evidence of alcohol or drugs

- Carrying out other tasks while driving

- Carrying passengers or heavy load

- Tiredness

- Aggressive driving, such as driving much too close to vehicle in front, racing, inappropriate attempts to overtake, or cutting in after overtaking

- Driving when knowingly suffering from a medical condition which significantly impairs the offender’s driving skills

- Driving a poorly maintained or dangerously loaded vehicle, especially where motivated by commercial concerns

Exceptional Hardship and 'Totting up' disqualifications 2020 Guideline

On 1st October 2020, a revised Magistrates’ Court Sentencing Guideline came into force.

The Sentencing Council published the following Response to consultation.

Exceptional hardship in ‘Totting up’ disqualifications

The issue

Where an offender incurs 12 or more penalty points on a driving licence, section 35 of the Road Traffic Offenders Act 1988 requires they must be disqualified for at least six months unless ‘the court is satisfied, having regard to all the circumstances, that there are grounds for mitigating the normal consequences of the conviction and thinks fit to order him to be disqualified for a shorter period or not to order him to be disqualified.’ The explanatory materials contained guidance for magistrates on how this should be applied but users had suggested that more information would be helpful.

The Council therefore consulted on a fuller explanation.

The responses and subsequent changes

This is the question in the consultation that provoked the most interest. In summary:

• Several respondents made suggestions that would require changes to legislation.

• Others simply agreed with the proposals.

• Some respondents felt that while the intention stated in the consultation was: ‘more

information on the procedure to be followed in such cases and guidance on the consideration of exceptional hardship applications would assist in ensuring that these are dealt with fairly, consistently and in line with legislation and case law’, the impact of the proposals would be to weaken rather than strengthen the test for exceptional hardship.

• Many magistrates wanted examples of what does and does not constitute exceptional hardship stating that otherwise decisions will continue to be inconsistent.

• Some respondents felt that the guidance did not accurately reflect the legislation or case law.

There were numerous suggestions as to how the explanation could be made clearer and more accurate. There were some points about which respondents gave conflicting views.

With regard to guidance on considering a discretionary period of disqualification, the Justices’ Clerks’ Society referred to Jones v DPP [2001] R.T.R 8 as authority for explicitly pointing sentencers towards imposing at least the totting ban by including:

if the court thinks that the defendant should be disqualified for the longer period under the totting up provisions, impose points and a totting disqualification. Where the defendant has persistently offended against Road Traffic laws, it is likely that the totting provisions will apply, rather than a discretionary disqualification

1 See for example, R v Roth [2020] EWCA Crim 967

Changes to the MCSG and explanatory materials, response to consultation 9 Whereas the Law Society said:

We note that the guideline also contains an often-missed point that a totting disqualification may be disproportionate and there is a possibility that a discretionary disqualification may be more appropriate.

It is important that the guideline is not too formulaic, otherwise it may remove the discretionary nature of imposing a disqualification and which may be to the detriment of a defendant who is trying to strongly argue for a discretionary period of short disqualification and where the tribunal considers this to be an appropriate sentence, and not disproportionate to impose the totting disqualification. In our experience it is an option most magistrates forget, and so having a reminder of the discretionary disqualification power in the guideline would be a useful reminder.

On the same point a magistrate suggested this form of words:

The court should take into account the seriousness of the offence and the offender's driving record in determining whether the threshold for a discretionary disqualification has been crossed. If this is not the case points should be imposed even if this results in the driver becoming liable to a totting disqualification.

One respondent suggested that ‘the guidance should make it clear that preference should be given to imposing a disqualification shorter than the ordinary minimum period rather than no disqualification at all, as per the power given in s.35(1) RTOA 1988; imposing no disqualification at all should be a highly exceptional occurrence, reserved only for the most highly exceptional cases.’

One magistrate felt that the guidance could be strengthened by a statement such as: ‘by their very nature successful applications for exceptional hardship will be rare’.

Several magistrates made the point that unrepresented offenders were at a disadvantage when seeking not to have a ‘totting’ ban imposed and that those who could afford a ‘clever’ lawyer would find a way to avoid disqualification. Others were concerned that notwithstanding the reference to the Equal Treatment Bench Book the circumstances of lower income offenders and their families (particularly in rural areas) would not be appreciated by many courts.

Several respondents felt that too much emphasis was put on ‘exceptional circumstances’ which makes it seem as though there is no other possible ground for avoiding or reducing the disqualification.

A barrister specialising in road traffic law pointed out that the proposed wording fails to identify that the burden of proof is on the defendant to the civil standard.

The Council carefully considered the various views and suggestions and agreed a revised version of the guidance that more closely reflected the wording in the legislation and incorporated several of the points made above, taking into account case law. The Council rejected the idea of providing examples of exceptional hardship as these will inevitably be case specific, but has incorporated more guidance on matters a court should take into account. Inevitably, because the revised guidance is more comprehensive, it is also longer but the Council is satisfied that it is as concise as it can be while still covering all the necessary points. It takes effect from 1 October 2020.

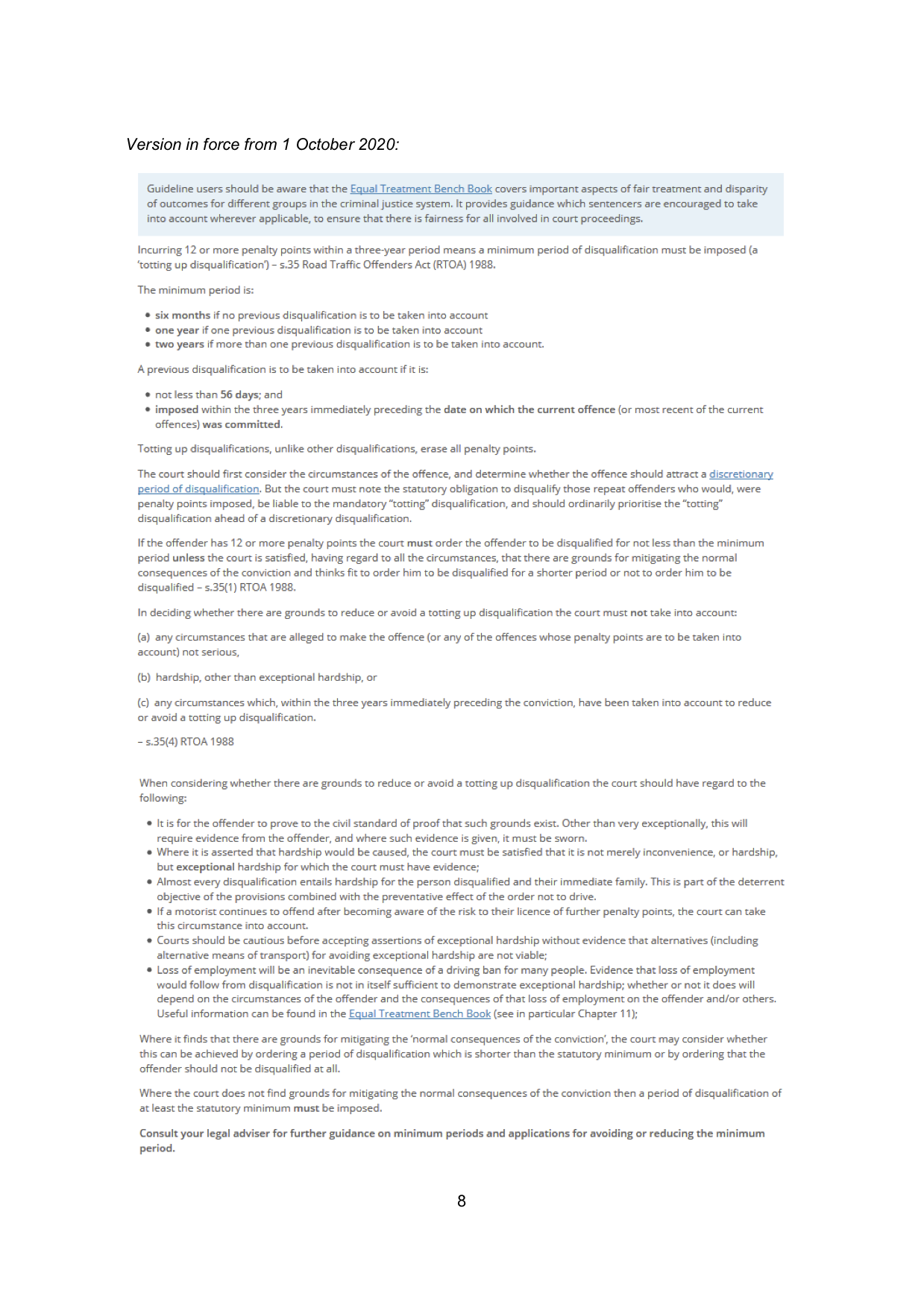

NEW GUIDELINE

Incurring 12 or more penalty points within a three-year period means a minimum period of disqualification must be imposed (a ‘totting up disqualification’) – s.35 Road Traffic Offenders Act (RTOA) 1988.

The minimum period is:

six months if no previous disqualification is to be taken into account

one year if one previous disqualification is to be taken into account

two years if more than one previous disqualification is to be taken into account.

A previous disqualification is to be taken into account if it is:

not less than 56 days; and

imposed within the three years immediately preceding the date on which the current offence (or most recent of the current offences) was committed.

Totting up disqualifications, unlike other disqualifications, erase all penalty points.

The court should first consider the circumstances of the offence, and determine whether the offence should attract a discretionary period of disqualification. But the court must note the statutory obligation to disqualify those repeat offenders who would, were penalty points imposed, be liable to the mandatory “totting” disqualification, and should ordinarily prioritise the “totting” disqualification ahead of a discretionary disqualification.

If the offender has 12 or more penalty points the court must order the offender to be disqualified for not less than the minimum period unless the court is satisfied, having regard to all the circumstances, that there are grounds for mitigating the normal consequences of the conviction and thinks fit to order him to be disqualified for a shorter period or not to order him to be disqualified – s.35(1) RTOA 1988.

In deciding whether there are grounds to reduce or avoid a totting up disqualification the court must not take into account:

(a) any circumstances that are alleged to make the offence (or any of the offences whose penalty points are to be taken into account) not serious,

(b) hardship, other than exceptional hardship, or

(c) any circumstances which, within the three years immediately preceding the conviction, have been taken into account to reduce or avoid a totting up disqualification.

– s.35(4) RTOA 1988

When considering whether there are grounds to reduce or avoid a totting up disqualification the court should have regard to the following:

It is for the offender to prove to the civil standard of proof that such grounds exist. Other than very exceptionally, this will require evidence from the offender, and where such evidence is given, it must be sworn.

Where it is asserted that hardship would be caused, the court must be satisfied that it is not merely inconvenience, or hardship, but exceptional hardship for which the court must have evidence;

Almost every disqualification entails hardship for the person disqualified and their immediate family. This is part of the deterrent objective of the provisions combined with the preventative effect of the order not to drive.

If a motorist continues to offend after becoming aware of the risk to their licence of further penalty points, the court can take this circumstance into account.

Courts should be cautious before accepting assertions of exceptional hardship without evidence that alternatives (including alternative means of transport) for avoiding exceptional hardship are not viable;

Loss of employment will be an inevitable consequence of a driving ban for many people. Evidence that loss of employment would follow from disqualification is not in itself sufficient to demonstrate exceptional hardship; whether or not it does will depend on the circumstances of the offender and the consequences of that loss of employment on the offender and/or others. Useful information can be found in the Equal Treatment Bench Book (see in particular Chapter 11);

Where it finds that there are grounds for mitigating the ‘normal consequences of the conviction’, the court may consider whether this can be achieved by ordering a period of disqualification which is shorter than the statutory minimum or by ordering that the offender should not be disqualified at all.

Where the court does not find grounds for mitigating the normal consequences of the conviction then a period of disqualification of at least the statutory minimum must be imposed.

Consult your legal adviser for further guidance on minimum periods and applications for avoiding or reducing the minimum period.

The Guideline is online here: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/explanatory-material/magistrates-court/item/road-traffic-offences-disqualification/3-totting-up-disqualification/

Wrong road on Notice of Intended Prosecution

Section 1 of the Road Traffic Offenders Act 1988 requires a warning of intended prosecution for various offences, including speeding. A written notice of intended prosecution must specify the:

- nature of the alleged offence; and

- time of the alleged offence; and

- place of the alleged offence.

Failure to comply with the s. 1 provisions is a bar to conviction. There is a legal burden on the defendant to prove non-compliance.

"A notice cannot be 'amended'; if time permits, a fresh notice should be served or sent in lieu of the defective one. It was said obiter in R. v Budd [1962] Crim. L.R. 49 that there can be a conviction for dangerous driving only if it occurred in the road named in the warning of intended prosecution. In Shield v Crighton [1978] R.T.R. 494 a notice erroneously stated the name of a road some 80yds distant from the road where the offence was committed; it was said obiter that a written document misstating the place could be misleading, but as an oral warning had been given at the scene at the time, what is now s.1 of the Road Traffic Offenders Act 1988 had been complied with." - Wilkinson's Road Traffic Offences.

"It is submitted that where an error in the notice is as to the place, it is a question of fact and degree whether the defendant has been misled and that a misstatement is not ipso facto fatal if the defendant has not been misled by the misstatement." - Commentary in Wilkinson's.

"If no oral warning of intended prosecution is given to a motorist at the time when it is alleged he has committed an offence to which (what is now s. 1 of the 1988 Act) applies, and if subsequently within the period of 14 days allowed by (what is now s. 1(1)(c) of the 1988 Act) he gets for the first time notice of the intention to prosecute him in the form of a written document which inaccurately says, for instance, that he was committing an offence on the M4 when he was actually committing an offence on the M1, that would produce a state of affairs in which the motorist would be misled and in which the purposes of the provisions of (what is now s. 1 of the 1988 Act) to give the motorist due warning of intended prosecution at a time when the facts of the case are still fresh in his mind would be defeated." - Shield v Crighton [1974] RTR 494.

What does it mean to be 'in charge' of a motor vehicle?

A common misconception surrounding drink-driving offences is that an offence is only committed behind the wheel of a moving vehicle.

It is possible to be convicted of a drink-driving offence merely by the fact that you were “in charge” of a vehicle while being above the legal limit.

There are three main road traffic offences related to the consumption of substances and being in charge of a vehicle:

in charge whilst unfit through drink (or drugs)

in charge whilst above the drink drive limit

in charge whilst above the specified drugs limit

“In charge”

Legislation does not define the concept of being “in charge” in this context. However, its meaning has been discussed in several cases. There is no hard and fast rule, but “in charge” is encompassed by two distinct classes of cases:

If the defendant was the owner or lawful possessor or had recently driven the vehicle, he would be “in charge”. The question that would be raised in his defence would be whether he had relinquished his charge (for example, whether he had put the vehicle in someone else’s charge).

If the defendant was not the owner, lawful possessor or recent driver, but was sitting in the vehicle or otherwise involved with it, the question for the court was whether he had assumed the role of being in charge of it. Usually this may involve having gained entry, but he may have manifested that intention in some other way, such as by stealing the keys of a car and demonstrating an intention to drive it.

Further circumstances that may also be taken into account include:

(a) whether and where he was in the vehicle or how far he was from it;

(b) what he was doing at the relevant time;

(c) whether he was in possession of a key that fitted the ignition;

(d) whether there was evidence of an intention to take or assert control of the car by driving or otherwise;

(e) whether any person was in, at or near the vehicle and, if so, the particulars in respect of that person.

It would be for the court to consider all these factors with any others that might be relevant and to reach its decision as a matter of fact and degree.

Driving or in charge whilst unfit

It is an offence to drive or attempt to drive a mechanically propelled vehicle on a road or other public place whilst unfit to drive through drink or drugs. Similarly, it is an offence to be “in charge” of a mechanically propelled vehicle.

You may be able to defend this if you can prove that at the material time the circumstances were such that there was no likelihood of you driving a mechanically propelled vehicle for as long as you remained unfit to drive through drink or drugs.

Driving or in charge above the limit

It is an offence if a person is in charge of a motor vehicle on a road or other public place after consuming so much alcohol that the proportion of it in his breath, blood or urine exceeds the prescribed limit. It may be presumed by analogy that as with offences under the same section of legislation, “consuming” is not limited to drinking, but that entry into the body other than by mouth is included.

A defence to this may arise if you can prove that the circumstances were such that there was no likelihood of you driving the vehicle whilst the proportion of alcohol in your breath, blood or urine remained likely to exceed the prescribed limit.

Driving or in charge above the specified drugs limit

It is an offence to be in charge of a motor vehicle on a road or other public place when there is a specified controlled drug in the your body.

However, as a defence to this, you may argue that:

(a) the specified controlled drug had been prescribed or supplied to you for medical or dental purposes,

(b) you took the drug in accordance with any directions given by the person by whom the drug was prescribed or supplied, and with any accompanying instructions (so far as consistent with any such directions) given by the manufacturer or distributer of the drug, and

(c) your possession of the drug immediately before taking it was not unlawful under section 5(1) of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (restriction of possession of controlled drugs) because of an exemption in regulations made under section 7 of that Act (authorisation of activities otherwise unlawful under forgoing provisions). You may wish to seek legal advice to help you to navigate these sections.

Wanton and Furious Driving

Wanton and furious driving is an offence arising from 19th century legislation used to prosecute offenders who do not fit the criteria of the more commonly used road traffic offences pursuant to more modern legislation.

The law

Section 35 of The Offences Against The Person Act 1861:

Whosoever, having the charge of any carriage or vehicle, shall by wanton or furious driving or racing, or other wilful misconduct, or by wilful neglect, do or cause to be done any bodily harm to any person whatsoever, shall be guilty of a misdemeanour, and being convicted thereof shall be liable, at the discretion of the court, to be imprisoned for any term not exceeding two years.

Who does it apply to?

The law applies to offences involving pedal cycles as well as other offences involving non-mechanically propelled vehicles (i.e. non-motorised vehicles such as a bicycle or horse-drawn carriage) that have not been incorporated into the Road Traffic Act, where bodily harm is caused to another. This offence pre-dates the advent of motor vehicles.

The prosecution has to prove that injury was caused to another person as a result of your “driving” (as mentioned, of a non-mechanically propelled vehicle). For example, in a relatively recent case, Charlie Alliston was charged with manslaughter and causing bodily harm by wanton and furious driving after he caused the death of a pedestian whilst riding a bicycle with no front brakes.

You may also face prosecution for this offence is when the alleged incident took place on private land or any other place where the Road Traffic Act does not apply.

What is the maximum sentence for causing bodily harm by wanton and furious driving?

The maximum sentence for causing bodily harm by wanton and furious driving is two years’ imprisonment.

Defences

There are several defences available to this offence. If you have been charged with wanton and furious driving, I am able to advise you on these.

Causing death by dangerous driving - Defences

“A person who causes the death of another person by driving a mechanically propelled vehicle dangerously on a road or other public place is guilty of an offence”

What is dangerous driving?

The court will consider you to have driven dangerously if you:

Drive in a way that falls far below that would be expected of a competent and careful driver, and;

It would be obvious to a competent and careful driver that driving in that way would be dangerous.

In this context, “dangerous” refers to danger either of injury to any person or of serious damage to property.

You will also be regarded to have been driving dangerously if it would be obvious to a competent and careful driver that driving the vehicle in its current state would be dangerous. As such, you can be convicted for dangerous driving on the grounds of your driving and/or the state of the vehicle when you are driving it.

What does the prosecution have to prove?

you were the driver;

you were driving a vehicle;

the vehicle was a “mechanically propelled vehicle”

the vehicle was driven dangerously;

you caused the death by driving dangerously ; and

you caused the death of another person. This can include causing the death of a passenger in your own vehicle.

Causation

You will be deemed to have caused the death of another due to your dangerous driving according to the following principles. You need not be the sole cause of the death, merely more than minimal; and the consequences of your driving will be examined. You may be convicted of the offence if the dangerous driving brought about a fatal incident as a consequence, such as parking your car in a dangerous location.

Alternative verdicts - what else could I be convicted of?

Dangerous driving

Causing death by careless driving

Careless driving

Wanton and furious driving

Sentence

The maximum sentence that you could receive is 14 years’ imprisonment. Disqualification for a minimum period of two years and endorsement are obligatory. An order for disqualification until you pass an extended driving test is also mandatory. If Special Reasons are found then 3 to 11 penalty points must be endorsed.

Sentence – assessing your case

The court will assess the “seriousness” of the offence in question. In doing so, they will take into account factors such as, but not limited to:

Your awareness of the risk;

The effect of alcohol and/or drugs;

The speed at which your vehicle was being driven;

Whether your behaviour left you “seriously culpable”;

An assessment of the victim (such as their vulnerability; were they a cyclist or pedestrian?);

Any aggravating factors, such as causing the death of more than one person; and

Evidence submitted to the court, such as police expert witness statements.

Factors that will be taken into consideration as mitigating factors include, but are not limited to:

A good driving record; and

Your conduct after the offence (such as giving assistance at the scene; and

Remorse

Defences for death by dangerous driving

The main arguments that can be presented to the court against a guilty conviction for death by dangerous driving are:

The driving was not dangerous - where there is insufficient evidence to establish that your driving was “dangerous” within the definition set out in he Road Traffic Act 1988.

Causation - where there is insufficient evidence to establish that your (dangerous) driving was “a cause” of death.

Automatism - where there is evidence to show that you were rendered unconscious or otherwise incapacitated from controlling the car (and therefore, you were not “driving”. For example, if you were to lapse into a coma;

Mechanical defect - a latent defect manifesting itself in the vehicle.

Necessity / duress

Self defence

ADVICE ABOUT CAUSING DEATH BY DANGEROUS DRIVING

The aforementioned is a very brief synopsis of a relatively complicated area of law. Information on a website is no substitute for expert professional advice. Please contact me for advice regarding your specific case.